Hi all,

I asked our students with AHSS summer research grants for an update about their progress and experiences. Kathryn’s project, focused on museums outside the Euro-American west, carried her to Qatar and London. Here’s her update from the summer swelter of the hot Qatari peninsula …

I winced as my Uber driver rolled the car slowly into another unavoidable pothole and the Camry’s entire frame jolted. We were out in the outskirts of Doha, the capital of Qatar, a small nation which sticks out like a cupped hand from top edge of the Arabian peninsula, extending into the gulf. Here, outside Doha, the city center’s smooth highways and improbably landscaped desert gardens faded out into bumpy cobblestone roads and migrant labor camps.

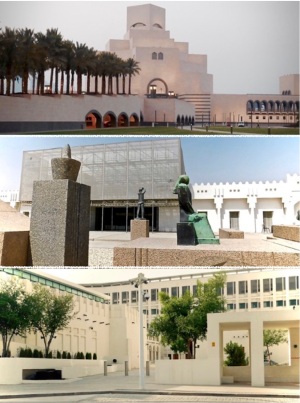

From top to bottom: The Museum of Islamic Art, Mathaf (the Arab Museum of Modern Art), and Msheirib.

All of the other museums I’d visited thus far had been set somewhere in Doha’s main downtown sprawl: the Museum of Islamic Art, placed in a white wedding cake of a building (which I.M. Pei had been brought out of retirement to design), standing on its own private island along the city’s park-lined shore; the Msheirib Museums, white-washed houses nestled into a quiet pocket of downtown between markets and skyscrapers; even Mathaf, the edgy Arab Art Museum, settled into the fabric of Education City’s foreign universities. None of these museums are further than 20 minutes from the compound where I was staying.

The Sheikh Faisal Bin Qassim Al Thani museum, on the other hand, lies far out into the desert. My iPhone’s maps were useless; my driver Jareesh and I were navigating using the tried and true method of asking random passers-by for the rough direction of the museum every couple hundred meters.

After a quarter of an hour meandering down thin roads between the walls of labor camps, I spotted the first sign for the museum, and Jareesh took me through the security and up to the front door of the museum, which was housed in an enormous castle of a building, standing amidst thin desert trees and the skeletons of boats.

Inside, the museum is packed with over 18,000 artifacts, ranging from art and calligraphy and religious objects to the Sheikh’s prized collection of hundreds of old cars. Thankfully,

Mahmoud, a museum tour guide, intercepted me at the front door and showed me around, allowing me to grasp the scale of the museum without becoming overwhelmed. It quickly became clear that this museum stood apart from the other collections I’d visited previously – this museum felt alive. Even during the slow summer days, other tourists and residents meandered around pointing at dramatic sailing ship displays and the deep oil wells around which the museum had been built at the end of the 20th century – if you lean over carefully, you can see the glimmer of oil far below at the bottom.

The arrangement of prominent – if somewhat austere – prestige museums in city centers, juxtaposed against beloved – if a bit well-worn – community museums, is a familiar one.

Over the past academic year, I’ve been researching museums in the Pacific Northwest, following the work of historian of anthropology James Clifford, who discussed the different types of museums in British Columbia in the chapter “Four Northwest Coast Museums,” of his book Routes.

Back at the end of May, I had begun the summer with a trip through the same four museums Clifford examined: the Royal British Columbia Museum (RBCM) in Victoria, the Kwagiulth Museum (now called the Nuyumbalees Cultural Centre) in Cape Mudge Village, the U’mista Cultural Centre in Alert Bay, and the University of British Columbia Museum of Anthropology (MOA) in Vancouver.

The RBCM and the MOA fit happily within the same museum model followed at Doha’s MIA, Mathaf, and the Msheirib Museums. These are all ‘Western’ in style, with tastefully minimalistic exhibits and careful, historical signage. They appear in tourist campaigns and are the subject of thousands of artful photos of their cities’ downtowns.

Museums like the Nuyumbalees Cultural Centre and the U’mista Cultural Centre – and the Sheikh Faisal Museum – are different. One of my contacts with the Qatari Museum Authority singled out Sheikh Faisal as one of the few truly ‘Qatari’ museums, founded by a member of the Al Thani royal family, on his own personal land, for the benefit of his friends and neighbors. The objects at Sheikh Faisal feel like personal belongings arranged on a shelf, precisely because they are; despite its size and grandeur, the Shiekh’s museum feels intimate. Museums like this one are further off the beaten path, but offer a look at how the people of a country truly see themselves.

And understanding what makes a museum ‘Qatari’ is vital at the moment, because the new National Museum of Qatar is scheduled to open in December, and it has big shoes to fill: according to nearly every source on the topic, the old National Museum, built in 1975, shortly after Qatar gained independence, was definitely beloved. That museum has been gone for decades, its artifacts in shortage, its signage literally scattered to the desert winds.

Now, it is the task of Sheikha Al Mayassa bint Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani, Chairperson of Qatar Museums, and her staff of both Qataris and foreign consultants, to construct a museum that brings together the best of both worlds – the new NMoQ will stand near the center of town, but it cannot feel like just another forbidding Western institution. It must be able, like a national flag or the Sheikh Faisal collection, to “represent the [nation] to its people, and its people to the world at large” (Roman Mars, TED2015 Vancouver).

I was reminded of the high stakes the new National Museum faces when Mahmoud pointed to a curiously shaped stone in a glass cabinet.

“You know the National Museum?” he asked.

I nodded.

“Do you know what this is, then?” he prompted me.

I thought back to my first glimpse of the new museum as I’d driven past it on the way from the airport. The jagged white curves and edges were shrouded in construction equipment, but lit up in the night. My housemate had laughed when I told her about this. “You mean the UFO?” she said. I came to understand that many residents of Doha saw something alien in the new construction of the National Museum – a worrying thing for its designer, who had been envisioning something entirely different. The museum’s architecture had been inspired by a natural geological form, found out in the sands beyond the city.

Back at the Sheikh’s museum, I nodded once more. “It’s a desert rose.”

Thanks so much for this wonderful update, Kathryn! We hope the rest of your stay there is productive. Safe travels, and we’ll see you back in Tacoma later in the summer.

Andrew